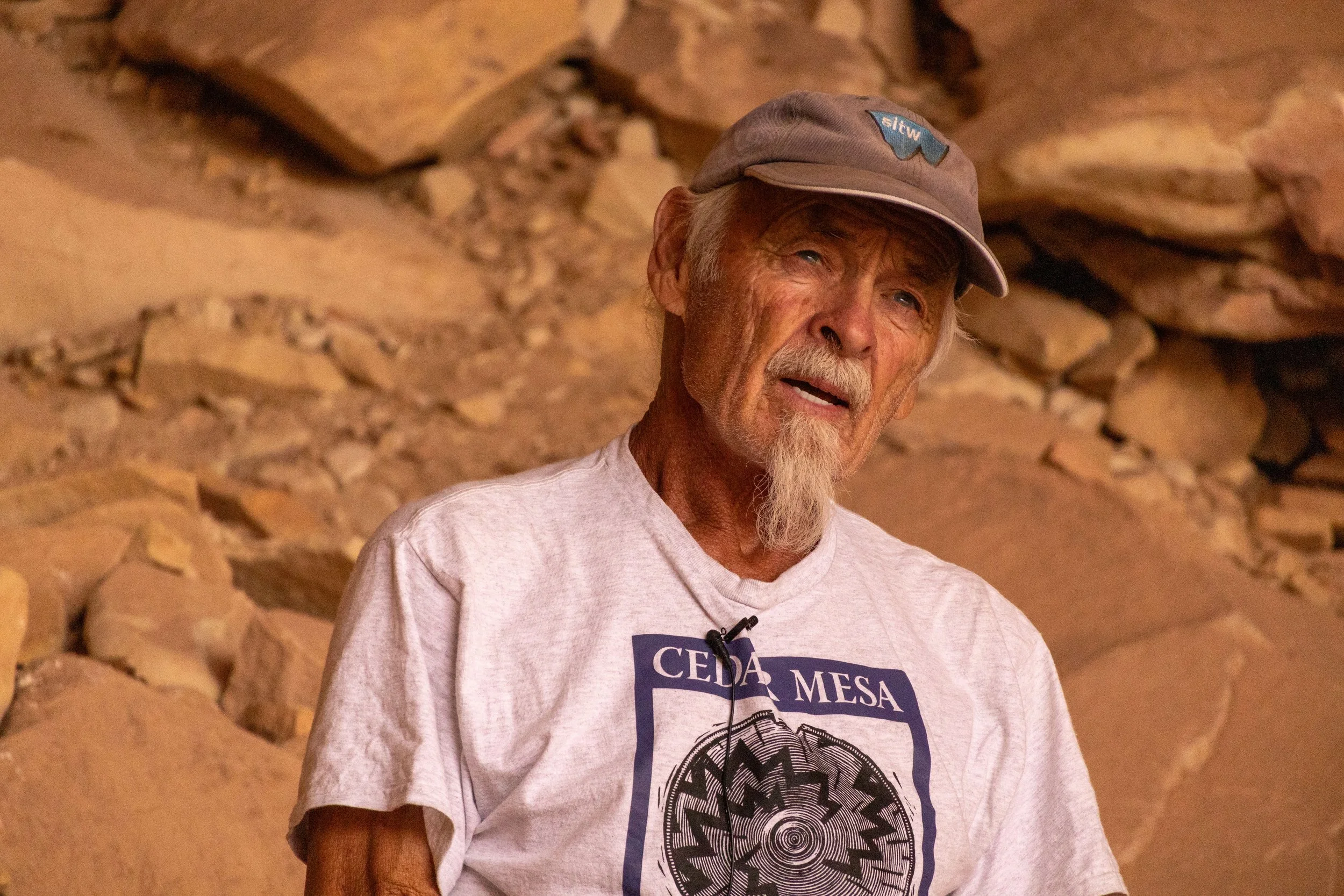

Russ’ love is undeniable. His warm smile a platform for his gray mustache to dance gleefully above his lip like a leaping salmon. His words slow down. With creased eyes and furrowed brows, he remembers his first time seeing a Chinook salmon. Standing on the shore, watching as it leaped out of the water, he said “Wow, that’s an amazing fish.” Decades later, it’s a rare sight in Central Idaho. Monolithic walls of concrete stand solemnly, seemingly uncaring, unaware, unmoving. Hundreds of feet high, these walls’ power is in their stature and their strength. They can’t feel, will never feel, will never see. They’ll never understand the leap of the Chinook as it travels hundreds of miles from river to ocean and back again. The salmon feel. They feel the cold concrete as they slam their heads up against it, hoping maybe this time it will give way. They feel their weary bodies running thin as the clock ticks down, time running out for them and their species.

An Emeritus Fisheries Research Scientist for the US Department of Agriculture, Russ Thurow knows salmon in ways that most of us, and I, do not. He took us to Marsh Creek, a pristine wetland in Central Idaho that’s almost as special to him as it is to the Salmon who journey hundreds of miles to it each year to spawn. The landscape is humble in its serene beauty, teeming with verdant grasses, beaver tracks, and clear, winding streams.

As Idahoan Chinook are increasingly threatened, Russ tells me that all the evidence points to blaming the dams. He explains, “The [Chinook] need a migration corridor to let them get to and from the ocean. They don't have that anymore. There's eight dams blocking them, 325, miles of reservoir that used to be free flowing river.” Even when their removal seems impossible, he’s refused to give up.

Walking with me down the winding creek, Russ points at a small discolored section of rocks at the bottom of the water. He identifies it as a Chinook redd, a nest for fertilized salmon eggs. Appearing as small depressions in the rocks and sediments of these streams, they’re almost impossible to notice, but Russ doesn’t have any trouble. Pointing at a newly created redd and talking about the female Chinook who built it, he says “That's a pretty big redd. Usually they're four to six feet long and three to four feet wide. This one is larger.” Larger, maybe, but still nearly imperceivable to someone who wasn’t looking for it. Even standing next to Russ, I could barely make out the boundaries he was describing.

Before creating their redds, these Marsh Creek Chinook need to complete a uniquely ambitious journey. For millions of years, salmon have been spawning in freshwater streams and growing as follow the river out to sea. They must survive this coast-bound trek, and then years in the ocean, eating to build energy for their return. If they’re still alive, they’ll be instictually pulled back to their spawning grounds by an internal magnetic compass and a scent stored in the recesses of their brain. As soon as they leave the ocean and enter freshwater, their bodies start to break down, necessitating an efficient return to their spawning habitat.

For a female Chinook born in Marsh Creek, a tributary to the Snake River, that journey is all the more treacherous. These salmon are climbing 6600 vertical feet from the Pacific Ocean along their journey home, one that spans 850-900 miles. Standing with the Sawtooth Mountains and the creek to his back, Russ makes it clear: “The fish here are the highest, climbing, longest, migrating Chinook populations on earth. No others do it.” Yet, all of her ancestors completed this journey that marked the culmination of their lives. Bearing the unfertilized eggs of her young, many obstacles stand in her way before those eggs can find themselves buried in a redd at Marsh Creek. She must have the fitness and energy to travel nearly 900 miles. She must avoid predators from below and from above.

She must also conquer a new challenge. In 1975, salmon numbers dropped dramatically after the completion of Lower Granite Dam, the fourth on the Snake River and the eighth along the Columbia River system. She doesn’t eat when she starts her journey back to the creek, burning fat for energy as her body runs thin. Swimming on a nutritional clock, she doesn’t have time or energy to spare. She churns slowly through the reservoirs created by the dams. She doesn’t know it, but the river that used to run free has become a mechanism that now taxes her every movement. She encounters one of these concrete walls and feels her body, scarlet red and bulging from fat reservoirs withering away in the warm, stagnant shadow of America’s power.

In 1992, Snake River Chinook salmon were officially listed in the Endangered Species Act. That year 12,700 wild Chinook returned to Idaho. Since then, Russ tells me, we’ve collectively invested more than $18 billion into their recovery throughout the Columbia basin. Last year, 7,200 fish returned. Hatcheries, weirs, and fish ladders all improve their chances of survival without demolishing the dams, but the salmon populations are hanging on by a thread. Yet, the fish don’t stop trying. She bangs her head up against the concrete statue, knowing where she needs to go but unable to get there. Her ancestors have leaped through these sections of the river for thousands of years. She perseveres, scaling the fish ladder only to find herself in another still reservoir. She has neither the energy nor the evolutionary fitness to trudge through the still water, but she doesn’t give up. Even with all of these obstacles, thousands of Snake River Chinook find their way back up the river each year. Remarkable in their adaptability, yet only able to stretch their energy so far, it’s a miracle that any of her species can survive the journey. She’s one of the lucky few to cross the dams on her way to her spawning grounds.

Exhausted, she wriggles up the riffles of the creek, shallow water sliding off of her now gaunt body. Not too deep, not too shallow, water at just the right speed, she’s found the perfect spot. Turning on her side, she writhes, flapping her tail up and down in the water, creating a vortex that pushes rocks and sediments out of the way to make room for her eggs. It was the last of her energy. She dies and her eggs die with her.

Russ’ voice held firm as he spoke. “That's just heartbreaking to see a fish that made it, but the eggs are still in her and she died.” It seems to only affirm his belief that the dams must meet their end. Salmon have been twisting and turning through the Columbia River and its tributaries for thousands of years, and for the first time, their end is truly in sight. Even with all of the obstacles standing in their way, they continue to survive. Russ knows change is needed soon, but he takes their perseverance as inspiration. Even when the individual dies, the species continues to fight up the rivers, past the dams, for hundreds of miles. Uncharacteristically, Russ could barely get the words out as he told us that he can’t give up. The salmon don’t give up, and as long as they keep fighting, so will he.